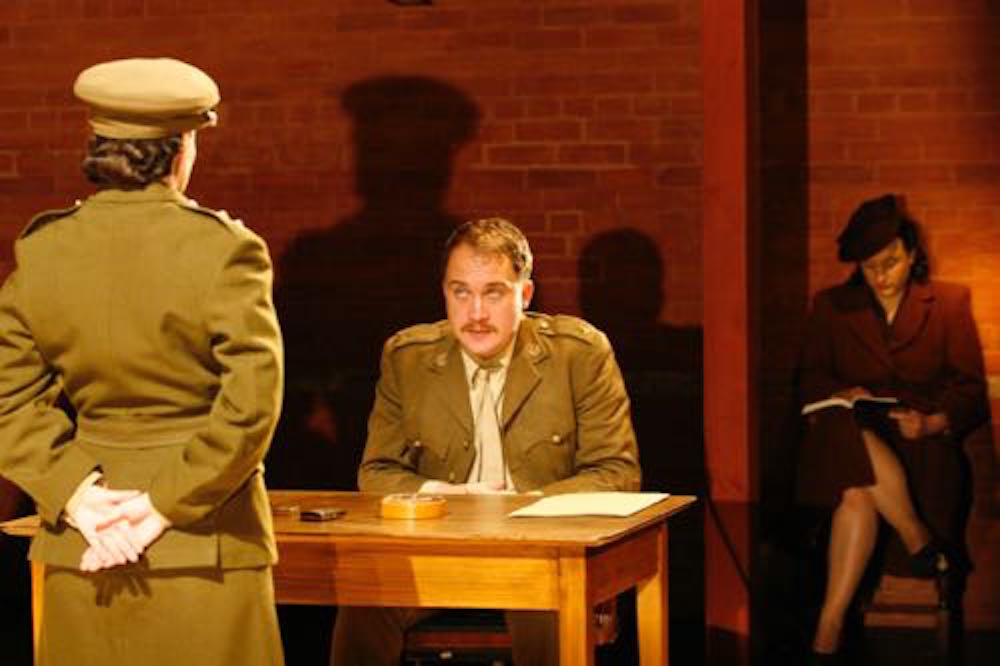

A vivid picture of post-war Britain and the often tender caution with which people began to rediscover their lives and each other, filled with the swing music and dance of its time.

A vivid picture of post-war Britain and the often tender caution with which people began to rediscover their lives and each other, filled with the swing music and dance of its time.

The Swing Left tells the story of six people finding their way in a radically changed world.

In overlapping narratives over one long weekend, a returning soldier struggles with the guilt of having spent the war as a POW, while the staff of his military hospital battle with traumas of their own; an aristocratic communist drunkenly heralds the dawn of a socialist Britain, while her insomniac brother waits for daybreak and company in a fog-bound railway station. Gradually their paths cross, secrets are shared and a figure from the past points the way home.

Eschewing an easy nostalgia, the show is still far from bleak. The play is suffused with the defiantly romantic music of the period and the characters too face their uncertain future with courage, passion and humour.

Written for the award-winning Unlimited Theatre, and developed through the Arts Council’s ‘Year of the Artist’ Project (2000) at Harrogate Theatre, Yorkshire, The Swing Left was also the inaugural production at the North Wall Arts Centre in Oxford in 2007.

From War of Nerves – Soldiers and Psychiatrists 1914-1994 by Ben Shepard

Extract from Chapter 21 – Prisoners of War

. . . Most POWs, it became clear from an experiment in 1944, denied having any problems and resented any suggestion that they were psychiatric patients. For any scheme to work, therefore, it would have to be voluntary, and employers and families would need to be ‘educated’ and staff carefully trained.

The outcome was the Civil Resettlement Units scheme. Some 20 communities were set up in the spring of 1945 in large houses around the country, which returning POWs could join, if they wished (60% did). Each unit took some 250 repatriated POWs for an average of about four or five weeks and gave them a period of temporary security, during which they could gradually resume responsibility for job and home life and regain some sense of their own worth and identity. The emphasis was very much on ‘social therapy’, and instead of army discipline, which POWs loathed, there was a loose, democratic structure intended to encourage men to ‘develop the self-control necessary for life in a civilised community’. Psychiatrists were involved, but mainly to orchestrate group discussions among the POWs; any suggestion that the POW had psychiatric problems or should seek psychiatric help was deliberately played down. At the same time, Wilson insisted that the staff be large enough to allow the inmates to be waited on at table, because research had shown that queuing for food aroused anxiety in ex-prisoners.

The American writer Paul Goodman once said that most good therapy is a combination of a whorehouse and an employment agency. The CRU scheme was outstandingly successful in re-integrating POWs into the labour force with retraining, ‘job rehearsals’ and vocational guidance. So far as one can tell, it also helped them emotionally: the medical literature paints a picture of men arriving like ‘hurt and lost children’ with the ‘dependent attitudes and primitive reactions of childhood’ – suspicious, insecure, irritable, full of guilt and resentment – and leaving a month later their confidence, self-respect and maturity regained. Doctors marvelled at the speed with which patients learnt to relate once more to women and to authority, like a limbless man learning to walk again. One man who had once seen ‘the social intimacies of the dance’ as ‘an unbearable provocation’ gradually developed the ‘capacity to derive pleasure from it’.

The psychiatrists attached most importance, however, to ‘the resocialisation of the individual’ in the CRUs: by taking part in group discussions, men would help each other in the various activities of the unit and be encouraged gradually to take social responsibility for each other. Doctors proudly described how at one unit a group of fifteen men who had refused to co-operate in communal activities and ‘were using the CRU as an easy-going hotel from which they could enjoy the neighbouring night life’ were persuaded by their fellow patients to stop making trouble – to replace ‘the external authority of military life with the self-discipline necessary in the civilian.’ […]

The Civil Resettlement Units were closed down in June 1946; they were very expensive to run at a time of public austerity. Besides, a War Office spokesman explained, ‘the majority of chaps were back at work. The last thing they wanted was to be reminded they were old POWs. There weren’t sufficient of them to fill the centres.’ […]

Final judgement on this episode is difficult. Clearly, mistakes were made and some FEPOWs got a raw deal. In theory the ‘social psychiatry’ pioneered at Northfield was inappropriate; individual psychotherapy would have worked better. But could much more have been done and would it have made a great difference? One doctor who has worked with FEPOWs doubts whether it would have been feasible to have offered all 37,000 more elaborate ‘de-briefing‘, especially as they themselves did not want it at the time – ‘if anyone had offered me “counselling” in 1945 I’d have been insulted’ recalls one. In many ways, it was precisely the old buttoned-up British tradition of suppressing emotion which got people through the wartime experience; switching off the anger and hatred could not be done quickly.

A contribution towards the understanding of the Repatriated Prisoner of War

Margaret G. Bavin, British Journal of Psychiatric Social Work vol 1, 1947-50

My first impression of the men was their analogy to hurt and lost children, they moved about the camp in small groups or singly with apparently unseeing eyes and expressionless faces, the “dead pan face” as it was called in their own language, which noted everything and gave away nothing. They seemed unable to mix, and afraid of being approached by or of approaching anybody who had not been through the same experiences, those in authority and women being viewed with the greatest suspicion […]

In the search for emotional security and in the attempt to solve the hidden conflict between the need to be loved and the dread of further rejection by individuals in a world which had already shown so much hostility, they were again thrown back on to infantile modes of behaviour and anti-social reactions. But whereas in captivity these reactions had the sanction of the group by virtue of their common manifestations as a means of self-preservation and of retaining a measure of self-respect, in a normal community their expression would have led and did lead to disapproval from those to whom they looked for love. The violence of their feelings and the fear of expressing them was a source of such anxiety to some men that they told me they were afraid to go into a public house for a drink as they were afraid of what they might do if they took offence when their self-control was weakened; others were quite incapable of doing anything positive unless like children they were told what to do, while at the same time they viewed with suspicion any external demand or request, suspecting the motive which might lie behind it. Many men related how violently they felt like reacting when their wishes were not immediately gratified […]

Women were a particular source of uncertainty and bewilderment; they were far from being the ideal, understanding, mother-figures of their dreams, and their changed attitudes, such as their independence, increased use of make-up, smoking and drinking, which were often taken as an indication of loose living, came as a great shock, and, together with the fact that many women were earning more than a man’s pre-war wage, were felt to constitute a threat to their manhood and aroused a fear that their place in the family was no longer necessary. The tenseness of the situation was in many cases almost unbearably increased by the reawakening of the sex impulse, often with heightened aggressive feelings where emotional insecurity was intense under prison camp conditions and on starvation diet it appeared that this impulse became inactive after the first few months; immediately on the return to a normal diet, however, it became reactivated with intensified demands for direct gratification.

February, 1947.

“An intriguing picture of post-war society with an unfamiliar setting ... As memory merges into history and the views of society underpinning the period are tested and challenged, historians have examined the society created in post-World War II England with microscopic detail. Steven Dykes and Unlimited Theatre, south from Leeds to help open new arts-space, The North Wall, see a parallel with 1997. There too, a new dawn brought a drizzly day of disillusion. ... As a look at the possibilities and tensions of 1946, this piece comes together as a strong social picture. The setting is one of the 20 Civil Resettlement Units that were established to help prisoners of war adjust to civilian life and work, particularly (and separately) to women and authority. ... This made the Units, through which thousands passed, potentially political. Men who had fought for a new society, and an electorate that had thrown out the Conservatives despite Winston Churchill’s war leadership, had expectations an impoverished government seeking social change in the teeth of institutional opposition could hardly meet. ... There’s richness in specific moments, and a vividly-edged individuality to each character ... Be patient and learn something of an often-overlooked part of the adjustment to post-war peace.”

Timothy RamsdenReviews Gate

”All I know is the war made me. You just have to get on and do things. It’s getting on and doing things, makes you realise what you can do.